DOI: https://doi.org/10.64010/CMEF2508

Abstract

It is now more evident than ever that society needs business leaders who seek more inclusive and sustainable economic models that lift people up rather than leaving them behind. According to Clifton & Harter’s (2019) It’s the Manager, the best life imaginable for young people and increasingly women doesn’t happen unless they have a great job and a manager or leader who encourages their development. Transformational leaders act as role models for their followers, motivating them through idealized influence, inspiration, individualized consideration, and intellectual stimulation, raising followers’ awareness about issues of consequence, shifting them to higher-order needs, and influencing them to transcend their own self-interest for the good of the group or organization. As leadership is an influence process and power is the potential to influence, this study examines relationships between French and Raven’s model of leader’s power and Kelman’s motives for follower conformity by invoking Bass’s model of transformational leadership as a mediating variable to better understand motives for conformity. The findings supported hypotheses that relationship between leader’s legitimate, referent, and expert power and followers’ identification and internalization were mediated by Bass’ full range of leadership model. Support for a fourth motive for conformity, obligation, being directly related to follower’s felt obligation to their organizational role and legitimate power and not leadership were also found. Implications for organizations and teaching leadership are made.

Introduction

The ACBSP 2021 Conference description states it is now more evident than ever that society needs business leaders who seek more inclusive and sustainable economic models that lift people up rather than leaving them behind. According to Clifton & Harter’s (2019) It’s the Manager, the best life imaginable for young people and increasingly for women doesn’t happen unless they have a great job and a manager or leader who encourages their development. Clifton & Harter defined a good job as working full-time with a week with a living wage. A great job included full-time employment, a living wage, being engaged in meaningful and fulfilling work, and experiencing real individual growth and development in the workplace. When asked, “How do you know you have such a culture,” the overwhelming answer was, “There is someone at work who encourages my development” (p. 6).

Analogous to creating quality products and services, the failure to maximize the potential of team members through inclusive leadership and economic growth is a defect (Clifton & Hater). In 30 years of U.S. and global research involving 160 countries and millions of in-depth interviews, Gallup found the most profound, significant, distinct, and clarifying finding is that 70% of the variance in team engagement is determined solely by the manager. The problem is that while volumes have been written about the science of management and leadership, the practice of management has not advanced significantly in the last 30 years (Clifton & Hater). It is no wonder then that only 15% of world’s workers are engaged at work and that Global GDP (and likewise personal buying power) has not increased. One way of conceptualizing whether followers’ potential is being maximized by manager’s behavior might be to consider a power and leadership perspective as antecedents to followers’ motives for conformity.

Despite the importance of power throughout history, we still do not understand how a leader’s power affects follower’s attitudes. Power is only the potential to influence (French & Raven, 1959), but does not tell us how leader’s act. (Yukl, 1994). Leadership theory characterizes leader behavior as the use of power (Bass, 1990; Hollander & Offermann, 1990; Yukl, 2002) and gives us some indication as to how leader’s power bases are likely to manifest. One way of understanding the process by which power affects follower’s outcomes is to adopt a leadership approach as recommended by Bass (1990), Hollander and Offermann (1990), and Yukl (1994). Leadership implies a group relationship between two or more persons, where one person by virtue of his or her behavior is identified as the “leader” and other group members are referred to as “followers.” According to Yukl (1994), leaders intentionally behave in such a way to influence the behavior of their followers. However, studies have concentrated on the use of leader’s influence tactics, such as inspirational appeals, consultation, rational persuasion, ingratiation, personal appeals, exchange, or pressure tactics (Falbe & Yukl, 1992), to explain follower’s motives for conformity with little attention paid to the relative effectiveness of leader’s behavior on follower’s motivation to conform and willingness to exert effort to accomplish the objectives. Thus, the goal of this study is to understand how the full range of leadership behaviors (Bass & Avolio, 1994; Arenas, Connelly & Williams, 2018) creates a greater sense of commitment by followers as measured by their motive for conforming to leader’s requests.

Interpersonal Power.

French and Raven (1959) defined reward power and coercive power as public-dependent power and legitimate power, referent power, and expert power as private-dependent power. The five power bases used in this study are:

Reward Power: A leader’s ability to influence behavior by creating feelings of dependence based on providing things followers’ desire.

Coercive Power: A leader’s ability to influence behavior by creating feelings of dependence based on providing things followers do not desire.

Legitimate Power: A leader’s ability to influence behavior by creating feelings of dependence based on followers’ feelings of obligation or responsibility.

Referent Power: A leader’s ability to influence behavior by creating feelings of dependence based on followers’ desire for personal acceptance or approval.

Expert Power: A leader’s ability to influence behavior by creating feelings of independence based on sharing information and expertise with followers.

Hinkin and Schriesheim (1989) developed and used a 20-item power scale that found reward power, legitimate power, referent power, and expert power demonstrated positive relationships with follower attitudes as measured by satisfaction, and coercive power demonstrated negative relationships with follower attitudes.

Motives for Conformity.

Kelman (1958) differentiated between three motives for conformity, in response to leadership: compliance, identification, and internalization.

Compliance occurs when a follower conforms out of a desire to obtain valued rewards or avoid punishment, but displays minimal effort and enthusiasm for the leader’s wishes,

Identification occurs when a follower conforms due to their attraction to or liking for the leader, and displays greater effort and a deeper level of commitment than compliance, and

Internalization occurs when a follower conforms based on goal congruence between the leader and the follower, and displays an even higher level of commitment, effort, and enthusiasm than either compliance or identification.

Yukl (1989) built a conceptual model of followers’ motives for conformity based on Kelman’s (1958) research on attitude change, however; there are attitudinal differences in Yukl’s outcomes versus Kel-man’s. Yukl defined three potential follower outcomes in response to leader behavior: resistance, compliance, and commitment. Yukl’s (1989) model therefore does not fully capture Kelman’s motive to conform out of attraction to or liking for the leader labeled as identification. This may be an important oversight as research on charismatic leadership in organizations suggests that followers frequently conform with leader’s requests because they are attracted to the leader (Kel-man, 1958). Moreover, additional research by Tepper, Eisenbach, and Percy (1995) on scales developed by Tepper (1993) to measure Kelman’s motives for conformity identified a fourth motive for conformity labeled obligation. Follower conformity based on Obligation is because of the follower’s felt obligation to their organizational role.

Transformational and Transactional Leadership.

Bass (1985) described a transactional leader as someone who “. . . provide[s] their subordinates with a clear understanding of what is expected of them and what they hope to receive in exchange for fulfilling these expectations” (p. xiii). Bass described a transformational leader as “someone who raised their awareness about issues of consequence, shifted them to higher-order needs, and influenced them to transcend their own self-interest for the good of the group or organization, and to work harder than they originally expected” (p. 29). The five behaviors from Bass’ full-range of leadership model included in this study are:

Contingent reward: Leaders use recognition and rewards for goals as motivating forces for its followers.

Idealized Influence (Charisma): Leaders instill pride and faith in followers by overcoming obstacles and confidently expressing disenchantment with the status quo.

Inspirational Motivation: Leaders inspire followers to enthusiastically accept and pursue challenging goals and a vision of the future.

Individualized Consideration: Leaders communicate personal respect to followers by giving them specialized attention and recognizing unique needs.

Intellectual Stimulation: Leaders articulate new ideals prompting followers to rethink conventional practice.

Bass’ (1985) conceptualization of transformational leadership includes dimensions of leader behavior not included in exchange-based theories allowing for greater explanatory power. According to Bass while transformational leadership builds on transactional leadership, a substantial body of literature suggests stronger relationships between transformational leader behaviors and follower outcomes compared to transactional leadership; including higher satisfaction, greater perceived leader effectiveness, greater effort, higher performance, and higher levels of trust (Bass, 1985; Percy, 1999). However, there is a dearth of research exploring relationships between leader’s power, leader’s behavior, and higher order levels of conformity as defined by Kelman.

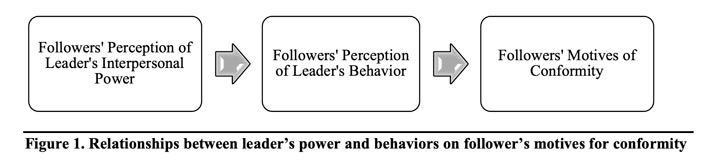

Accordingly, this study invokes Bass’ (1985) transactional and transformational leadership model as the key variable to explain how followers’ perceptions of leader’s power affects followers’ motives for conformity as depicted in Figure 1.

Hypotheses

There are numerous ways in which power might influence followers’ motives for conformity as shown in Figure 1. First, power may directly influence follower motives for conformity. Second, leader’s power bases may influence followers’ motives for conformity directly and indirectly. That is to say, the total effects may be due to a combination of direct (unmediated) effects and indirect effects working through leadership as a mediator. Finally, as power is the perceived ability to exert influence, a third possibility is that power indirectly influences follower motives through the mediated effects of leadership. While extant empirical research suggests direct relationships between leader’s power bases and satisfaction and between transactional and transformational leadership and satisfaction, it is more likely that power only indirectly affects followers’ motives for conformity through leader’s behavior because power is the capacity to influence and leadership is an influence process (Bass, 1985).

Relationships between reward and coercive power, leadership, and compliance.

Relationships between leader’s reward power and coercive power and followers’ compliance as a motive for conformity may be explained by invoking Bass’ (1985) sub-dimension of transactional leadership termed contingent reward. According to French and Raven (1959), reward and coercive power are public-dependent leader-follower relationships, relationships that can best be explained by transactional leadership. Transactional leadership is a process of contingent reinforcement, where the leader and follower agree on what the follower must do to be rewarded or to avoid punishment. Tepper (1993) found that transactional leaders were more likely to use exchange tactics than were transformational leaders. In addition, Tepper (1993) found that transactional leaders were also more likely to use pressure tactics than were transformational leaders. Falbe and Yukl (1992) found that the use of pressure tactics resulted in resistance. Contingent reward leadership reflects an exchange-based relationship between leader and follower. Rewards directly or indirectly can be provided by leaders, or conversely, leaders can impose penalties for failing to achieve goals.

Hypothesis 1: Leader’s use of contingent rewards mediates the positive relationships between leader’s reward power and followers’ compliance as a motive for conformity.

Hypothesis 2: Leader’s use of contingent rewards mediates the negative relationships between leader’s coercive power and followers’ compliance as a motive for conformity.

Relationships between legitimate and referent power, leadership, and identification.

The relationship between leader’s legitimate power and followers’ identification as a motive for conformity may be explained by invoking Bass’ (1985) idealized influence and inspirational motivation, that Tepper & Percy (1994) labeled charisma. According to French and Raven (1959), legitimate power is a private-dependent relationship, a relationship that will be explained by charisma. Charisma, as originally invoked by Weber (1947), was used to describe a form of authority and influence based on followers’ perceptions of the leader being endowed with special gifts. Private-dependent influence, of which legitimate power is a form, cannot be observed by the power agent or leader. That is to say, one cannot base a legitimate relationship on the exchange that takes place between leader and follower. Rather, a leader’s legitimate power is based on the followers’ trust in and respect for the leader (a private (and dependent) response, rather than a public response). Charismatic leaders, according to Bass and Avolio (1994), are admired, respected, trusted, and serve as role models for their followers. House (1977) states that followers willingly and unquestionably obey charismatic leaders. Furthermore, because charismatic leaders often arise in times of crisis, charisma is often routinized by the development of rules, arrangements, and shared meanings to achieve stability (Bass, 1985; Weber, 1947).

Hypothesis 3: Leader’s use of charisma mediates the positive relationships between leader’s legitimate power and followers’ identification as a motive for conformity.

Referent power is based on a private-dependent relationship. Therefore, one way to explain the relationship between leader’s referent power and followers’ identification as a motive for conformity is to invoke charisma, which is being defined in this study as a combination of idealized influence and inspirational motivation (Tepper & Percy, 1994). Charismatic leaders act as role models for their followers, while followers identify with and want to emulate them (Bass & Avolio, 1994). Kelman (1958) stated that followers accept the influence of charismatic leaders in order to identify with them. Thus, while followers’ feelings for the charismatic leader are private, they also depend upon the leader to define their sense of identity. Charismatic leaders define roles in ideological or visionary terms that appeal to followers’ growth needs (Bass, 1985) and, according to House (1977), followers of charismatic leaders share similar beliefs and show affection for their leader.

Another sub-dimension of transformational leadership that may be invoked to explain the relationship between leader’s referent power and followers’ motives for conformity is individualized consideration. Individually considerate leaders pay special attention to each followers’ needs for achievement and growth by acting as a coach or mentor. Leaders demonstrate acceptance of individual differences, involve their followers in two-way communication, and see their followers as whole persons, rather than just as employees. Subordinates are more likely to model their own leadership behavior after their superior if they see their leader as someone who is successful, competent, and considerate (Bass, 1985).

These two characteristics of transformational leadership-charisma and individualized consider-ation-will explain relationship with referent power, since referent power is based on the ability of a leader to mediate feelings of personnel acceptance and liking (Hinkin & Schriesheim, 1989).

Hypothesis 4: Leader’s use of charisma and individualized consideration mediates the positive relationships between leader’s referent power and followers’ identification as a motive for conformity.

Relationships between expert power, leadership, and internalization.

Intellectual stimulation may be invoked to explain the relationship between a leader’s expert power and followers’ internalization as a motive for conformity. Intellectually stimulating leaders depend upon sharing their expertise and information as a source of power. Considering their information, knowledge, and expertise, intellectually stimulating leaders provide new ways for their followers to look at old problems. Numerous scholars have noted that followers are empowered by the effects of information, that is to say followers are enabled to make decisions and complete tasks on their own, because they now have the power (information) to do so (Conger & Kanungo, 1988).

Hypothesis 5: Leader’s use of intellectual stimulation mediates the positive relationships between leader’s expert power and followers’ internalization as a motive for conformity.

Relationships between legitimate power, leadership, and obligation.

Kelman and Lawrence’s (1972) description of Lieutenant William Calley’s conformity captures subordinate’s obligation to the job and the organization: “an individual [such as Lieutenant Calley] is bound to the system by virtue of the fact that he accepts the system’s right to set the behavior of its members within a prescribed domain” (p. 204). Followers’ motive to conform when defined by obligation is linked to behaviors that are expected and considered a responsibility. Therefore, obligation does not imply acceptance of the act itself, as does internalization, rather obligation involves acceptance of the broader context in which managers exercise influence. The follower is not expecting rewards, being liked, or feeling a sense of shared goals, but merely meeting their responsibilities. Therefore, obligation is more likely to result directly from followers’ acceptance of the legitimate power of the leader, rather than indirectly from leadership behavior.

Hypothesis 6: Followers’ perception of a leader’s legitimate power will predict obligation as a motive for conformity directly rather than mediation through leader behavior.

Methods

Participants. The hypotheses were tested using a field study method. Data was collected from members of an Air National Guard (ANG) unit located in the Southeast employed in administrative, technical, professional, and managerial positions. Respondents completed the survey questionnaire during a human relations class that all members of the Air National Guard (ANG) are required to attend. Respondents completed the survey using their immediate ANG supervisor, and were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. The total number of members of the base is 1,241 and 250 individuals completed the survey (20.1%). Of the 250 individuals, three did not return their survey at the end of the class and 15 surveys contained incomplete data, resulting in 232 usable surveys. The average age of the respondents was 36.7 years of age and 87.1% were males.

Materials and Procedures.

The survey instrument for this study included Hinkin and Schriesheim’s (1989) scales to measure followers’ perceptions of their boss’s power bases, a modified version of Bass and Avolio’s (1990) scales to measure transactional and transformational leader behaviors (Tepper & Percy, 1994), a 20-item scale developed by Tepper (1993) and refined by Tepper, Eisenbach, & Percy (1995) to measure followers’ motives for conformity.

Power Scales.

Reward power, coercive power, legitimate power, expert power, and referent power were measured using Hinkin and Schriesheim’s (1989) power scales. Schaffer, Tepper, and Percy, (1996) found further support for the validity of Hinkin and Schriesheim’s (1989) five-factor model. Schaffer, Tepper, and Percy (1996) also demonstrated that a two-factor model consisting of position power (reward, coercion, and legitimate power) and personal power (referent and expert power) was not supported by the data, thus further supporting the use of French and Ravens five power bases individually. Respondents were asked to indicate the kinds of resources their boss had to get them to do the things he/she wanted using a 5-point scale with “5” being strongly agree and “1′ being strongly disagree. Sample survey items as are follows: Reward, increase his/ her subordinate’s pay levels; Coercive, make things unpleasant for his/her subordinates; Legitimate, make his/her subordinates feel that they have commitments to meet; Referent, make his/her subordinates feel like he/she approves of them; and Expert, give good technical suggestions to his/her subordinates.

Leadership scales.

Tepper and Percy (1994) assessed the structural validity of the MLQ using maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis. They found support for a four-trait model in which idealized influence and inspirational motivation loaded on the first factor, which they labeled charisma, intellectual stimulation loaded on the second factor, individualized consideration loaded on the third factor, and contingent rewards (promises and rewards combined) loaded on the fourth factor. As Bass (1985), originally labeled Idealized Influence Charisma, Tepper & Percy (1994) used Charisma based on their findings that idealized influence and inspirational motivation appear to capture one construct, not two.

Therefore, Tepper and Percy’s (1994) 30-item version of Bass and Avolio’s (1990) 72-item MLQ Form-X was used. Tepper and Percy (1994) selected the 30 items because they met the following criteria: (1) the content of the items was consistent with Bass’s (1985) definitions, (2) the items served as measures of leadership behavior rather than outcomes of leader behavior, and (3) the items had been good indicators in previous research. Respondents indicated how frequently their boss displayed the behaviors described in each item using a 5-point response scale with “5” being frequently and “1” not at all. Sample items as are follows: Contingent Rewards, tells me what to do to be rewarded for my efforts; Charisma, encourages me to take risks and persuades me about the importance of the task or mission; Individualized Consideration, works with me on a one-on-one basis; and Intellectual Stimulation, arouses my curiosity about new ways of doing things.

Motives for Conformity scales.

Respondents completed Tepper, Eisenbach, and Percy’s (1995) refined version of Tepper’s (1993) 15-item scale to measure Kelman’s (1958) motives for conformity instrument. The revised 20-item instrument measures Kelman’s three motives, compliance, identification, and internalization, and added a fourth motive obligation. Using confirmatory factor analysis, the five items written to measure compliance appeared to measure two distinct constructs-compliance as involving conformity motivated by fear or punishment and obligation as motivated by obligation to the job or organization. Testing of the viability of a four-factor model using confirmatory factor analysis provided a better fit to the data than the three-factor model.

Respondents were asked to describe a situation when their boss asked them to do something at work in the last four weeks and why they complied with the request using a 5-point scale with “5” being strongly agree and “1” being strongly disagree. Sample items are as follows: Compliance, I could have gotten in trouble if I had refused; Obligation, I felt obliged to perform the activity because it was my duty; Identification, I like my boss; and Internalization, I was convinced that what was asked of me was important.

Multiple Regression Analysis

The hypothesized mediation effects of transformational and transactional leadership were assessed following the steps outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986). According to Baron and Kenny, evidence that a variable (M-Leadership) fully mediates the effects of a predictor variable (X-Power) on a criterion variable (Y-Motives for Conformity) is demonstrated when all the following criteria are met:

Step 1 – power (x) demonstrates a significant relationship with motives for conformity (y);

Step 2 – power (x) demonstrates a significant relationship with leadership (m);

Step 3 – leadership (m) demonstrates a significant relationship with motives for conformity (y); and

Step 4 – when both power and leadership are regressed on motives for conformity, the power variable becomes insignificant, the leadership variable continues to demonstrate a significant relationship in a full mediation model, and the percent of variance explained (r2) increases significantly from step 1.

Results

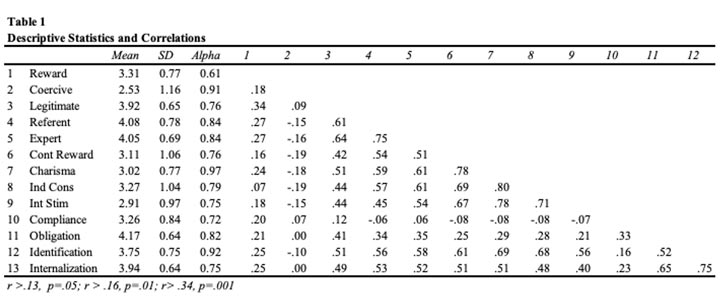

Correlations and reliabilities. Table 1 reports the scale means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliabilities for the study variables. These results emphasize three points. First, all the scales obtained acceptable alpha coefficients (greater than .70; Nunnally, 1978), except for the reward scale (a = .61). Schaffer, Tepper, and Percy (1996) identified issues with Hinkin & Schriescheim’s item 3 of the reward scale that impacts reward’s internal consistency. Second, the signs on the significant correlations between the power scales, leadership scales, and the motivation for conformity scales revealed relationships generally consistent with the hypotheses. One exception is that none of the leadership behaviors demonstrated a significant relationship with compliance as a motive for follower conformity.

Multiple Regression Results.

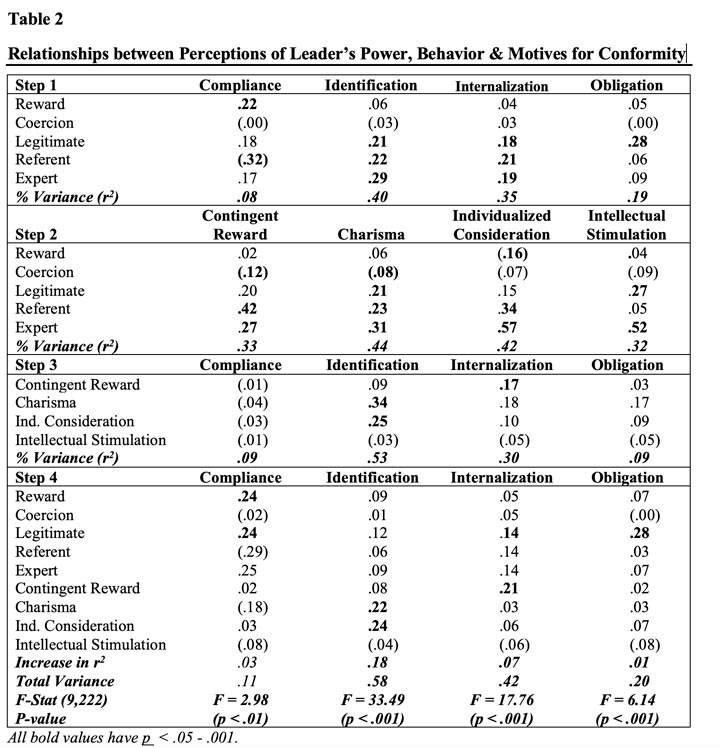

The multiple regression results shown in Table 2 suggest partial support for the theoretical model and overall the interrelationships among followers’ perceptions of leader’s power, leader’s behavior, and followers’ motives for conformity and are consistent with the mediation model depicted in Figure 1.

Hypothesis 1. While reward power demonstrated significant relationships with compliance in step 1 (ß reward = .22, p < .05), the non-significant relationship between reward power and contingent reward in step 2, (ß reward = .02, p = n.s.) failed to support Hypothesis 1 that leader’s use of contingent rewards would mediate the positive relationships between leader’s reward power and followers’ compliance as a motive for conformity. Moreover, contingent reward in step 3 failed to demonstrate a significant relationship with compliance (ß contingent reward = (.01), p = n.s.).

There is the likelihood that the effects of power and leadership may interact to influence the relationships between power and compliance as step 4 demonstrated a small improvement in r2 and improved positive relationships between compliance and reward (ß reward = .24, p < .05), legitimate (ß legitimate = .24, p < .05), expert (ß expert = .25, p < .05;) power, and a negative relationship between compliance and referent power (ß referent = -.29, p < .05).

Hypothesis 2. While coercive power demonstrated a significant negative relationship with Contingent Reward (ß coercive = (.12), p <.05) in step 2, Hypothesis 2 that leader’s use of contingent rewards would mediate the negative relationships between leader’s coercive power and compliance was not supported as coercive power failed to demonstrate any significant positive or negative relationship with any of the four motives for conformity in step 1. In addition, coercive power also demonstrated a significant negative relationship with charisma (ß coercion = -.08, p < .05).

Hypothesis 3. Support for followers’ perceptions of leader’s use of charisma as mediating the positive relationships between leader’s legitimate power and followers’ identification as a motive for conformity was supported. As per Table 1, step 1 demonstrated significant relationships between legitimate power and identification (ß legitimate = .21, p < .05); in step 2 between legitimate power and charismatic leadership (ß = .21, p < .05); in step 3 between charisma andlegitimateidentification (ß charisma = .34, p < .001); and in step 4 legitimate power becomes non-significant in the presence of leadership while charisma remained significant (ß legitimate charisma = .21, p =n.s.; ß = .22, p < .05). In addition, there is a large increase in the amount of variance explained from step I to step IV (40% to 58%).

Hypothesis 4. Support for followers’ perceptions of leader’s charismatic and individualized consideration leadership behaviors acting as mediators between leader’s referent power and followers’ identification as a motive for conformity was fully supported. In step 1, referent power demonstrated a significant relationship with identification (ß referent = .22, p < .01); in step 2 referent power demonstrated significant relationships with both charismatic leader behavior (ß referent = .23, p < .01; ) and individualized consideration leader behavior (ß referent = .34, p < .001); in step 3 between charisma and identification (ß charisma = .34, p < .001) and between individualized consideration and identification (ß charisma = .25, p < .001); and in step 4 referent power (ß referent = .06, p =n.s.) becomes non-significant in the presence of leadership, while charisma (ß charisma = .22, p < .01) and individualized consideration (ß ind. cons. = .24, p < .001) remained significant. In addition, there is a large increase in the amount of variance (r2) explained from step I to step IV (40% to 58%).

Hypothesis 5. The mediation model that intellectual stimulation would mediate the relationship between expert power and followers’ internalization was not supported, although support for contingent reward mediating the relationship between referent/ expert power and internalization was found.

Regarding hypothesis 5, while expert power (ß = .09, p < .05) demonstrated significant relation-expertships with internalization in step 1 and with intellectual stimulation in step 2 (ß expert = .52, p < .001), intellectual stimulation was not significantly related to internalization (ß int.stim. = (.05) p =n.s.) in step 3. However, in step 3 contingent reward demonstrated a significant relationship with internalization (ß con. reward = .17, p < .01). As stated above expert power, as well as referent power, demonstrated significant relationships with internalization (ß expert = .19, p < .05; ß referent = .21, p < .001) as well with contingent reward in step 2 (ß = .27, p < .05; ß referent = .42, p < .001). Final-expert ly, in step 4, both referent and expert power become non-significant, while contingent reward remained statistically significant (ß = .21, p < .001), and con. reward the percent of variance explained (r2) goes from 35% to 42%.

Hypothesis 6. As demonstrated in Table 1, followers’ perception of a leader’s legitimate power predicted obligation as a motive for conformity directly rather than indirectly mediated by leader behavior. The significant, positive relationship between legitimate power (ß legitimate = .28, p < .01) and obligation in step 1 and non-significant relationships between leader’s behavior and obligation in step 3 and 4, both with and without the presence of leadership, demonstrates a direct relationship between legitimate power and obligation.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to develop and test a model of the relationships between leader’s power bases and followers’ motives for conformity as a means of understanding how business leaders lift people up-both by inclusivity (development of all followers) and economically. Consequently, transactional and transformational leader’s behavior was invoked as the key mediating variable between power and follower conformity, and the results suggest evidence of interrelationships consistent with mediation (Baron & Kenny, 1986) and the theoretical model.

Relationships between reward and coercive power and compliance were not observed as expected. While reward power represents the ability to influence behavior by creating feelings of dependence based on providing things followers’ desire, the results of the analyses demonstrate that the potential to reward does not necessarily relate to what followers consider leadership, as the only leader behavior related to reward power was a negative relationship with intellectual stimulation. In addition, no leadership behavior demonstrated a relationship with compliance. As is the case in many organizations, managers or leaders often do not have the direct ability to reward or punish behaviors outside of the systems developed by the organization to award promotions or raises.

The relationships between legitimate power and identification were explained by leader’s charismatic behavior and individualized consideration. This hypothesis may have seemed counterintuitive; however, charisma has been labeled both as a form of power or authority (i.e., the potential to influence; Yukl & Falbe, 1991) and as a form of leader behavior (i.e., influence in action; Bass, 1985). Conger (1993) argues that for a charismatic leader to be influential he or she must be successful. Successful charismatic leaders create a new, institutionalized order. Thus, the paradox of charismatic leader behavior is that its success results in forms of bureaucracy and traditions that rise up and ultimately consume it (Conger, 1993). Therefore, long-term charismatic leadership is a continuous process whereby the leader on the one hand creates new orders, while on the other hand moves on to challenge existing institutionalized orders. In both cases, followers perceive that the charismatic leader legitimately has the right to expect them to follow.

While charisma was related to referent power, unexpectedly contingent reward was also linked to referent power as a means of explaining follower identification. One explanation for contingent rewards mediating the effect on identification is that followers who “like” their leader do so because the leader also rewards their behavior. That is to say, reward power is the ability to reward, whereas contingent reward leadership actually tells the follower what they need to do to be rewarded and actually provides rewards. However, clearly further research needs to be conducted to better understand the relationships between reward power and follower outcomes.

The failure of intellectual stimulation to explain expert power, while contingent reward, charismatic leadership, and individualized consideration explained the perceptions of expert power on internalization was the most surprising result. Falbe & Yukl (1992) found that the use of rational persuasion was as likely to result in compliance as it was resistance, and therefore the overuse of rational persuasion may override the effects on internalization. It is also somewhat unexpected as the strongest relationship in Table 2 is between expert power and internalization. Another likely explanation is multi-collinearity between identification and internalization. When evaluating Table 1’s correlations, first note that the strongest correlation is between identification and internalization and second that identification has a stronger correlation between expert power than does internalization. Finally, one explanation is that the study participants were members of an Air National Guard unit and that “rethinking new ways of doing things” may not always be appropriate when working on jet engines.

Direct relationships between legitimate power and follower conformity based on obligation were observed as expected. Because of the subordinate’s felt obligation to their organizational role followers’ motive to conform when defined by obligation is linked to behaviors that are expected and considered a responsibility. Therefore, obligation does not imply acceptance of the act itself, as does internalization, rather obligation involves acceptance of the broader context in which managers exercise influence. The follower is not expecting rewards, being liked, or feeling a sense of shared goals, but merely meeting their responsibilities. Therefore, obligation is more likely to result directly from followers’ acceptance of the legitimate power of the leader, rather than indirectly from leadership behavior.

It appears from the two distinct outcomes regarding legitimate power that it may have two distinct perceptions in the eye of followers. First, followers may demonstrate respect for the leader and conformity in the form of identification, because they perceive the leader as having earned the right to be appointed to that position. Second, followers may demonstrate conformity in the form of obligation because of respect for the position regardless of who is the in the position.

Moreover, understanding followers who act out of a sense of obligation rather than compliance or internalization as did Lieutenant Calley in the My Lai massacre, or the participants in the Milgram studies where 60% administered what they thought were dangerous levels of electricity, may help us to better understand the senseless and violent killing of George Floyd. Former U.S. President Barack Obama said the protests over Floyd’s death represented a “genuine and legitimate frustration over a decades-long failure to reform police practices and the broader criminal justice system” (Cuddy, 2020).

The majority of police officers exist to serve and protect, as was demonstrated in the Nashville bombing when police officers rushed into clear residents before the explosion, saving the lives of residents. As Mayor John Cooper put it, “They may consider what they did as just a regular part of their duties, but we in Nashville know it was extraordinary” (Jorge, 2021). Police Chief John Drake described their actions, “Immediately they didn’t think about their own lives, they didn’t think about protecting themselves, they thought about the citizens.” Yet, unfortunately there are those officers, acting out of obligation to what they see as their job, commit horrendous actions in what they perceive as the accomplishment of that job.

Wiltermuth and Flynn’s (2013) research on power, moral clarity, and punishment may add to our understanding of the tragic killing of George Floyd. First, people with power may take harsh action to demonstrate their power because by punishing others they provide evidence of their power. Second, powerful people tend to punish transgressors more severely because they are accustomed to having their decisions accepted unquestionably. Third, powerful people may increase severity of punishment because powerful people use stricter moral standards. While Wiltermuth and Flynn’s research was organizationally based, it appears to offer explanatory rationale for why some may act with excessive force, as was the case in the killing of George Floyd.

Implications for Organizations

There are implications for organizations regarding employees who act out of obligation. Employees may not always behave in a way that is appropriate in their treatment of others because they see as their duty and obligation to protect the organization, often resulting in rigid application of policies that negatively affect both customers and teammates, resulting in damaged employee morale, manager’s and firm’s reputations, team productivity, and loss of business.

On a more positive note, the research supports that training and developing organizational leaders in the full range of leadership behaviors will result in employees who are engaged and committed to the organization. This will occur because the organization is committed to developing its employee’s full potential, resulting in identification and internalization as a motive for conformity versus compliance. As Clifton and Hater (2019) argue, fully engaged employees, who are engaged because someone encourages their development, will create an economic transformation-that creates inclusive and economically sustainable models.

Implications for Teaching

The full range of leadership model (Bass & Avolio, 1994) results in leaders who through individualized consideration encourage continuous development and growth of followers; intellectual stimulation encourages the imagination of followers; inspirational motivation aligns individual and organizational goals and needs; and idealized influence develops trust and confidence among followers. Gallup’s research demonstrating 70% of the variance in team effectiveness is due to the manager/leader and this study’s findings that transformational leaders create higher order commitment, as educators we should therefore consider the importance of helping our students develop the full range of leadership qualities.

Management curriculums typically base the study of leadership on one chapter in a management class and supporting textbooks. Therefore, it should not be surprising that our students do not graduate with leadership skills. To accomplish this business faculty will need to do more than describe and test leadership theory, but rather teach leadership theory as well as improve the ability to apply theory through critical thinking and development of individual leadership skills and self-awareness (Lussier & Achua, 2016).

Leadership can be taught (Parks, 2005).

The development of the full-range of leadership skills most likely will not occur in a traditional lecture-based classroom, but in a flipped classroom where the study of leadership occurs outside the classroom and the application occurs in the classroom. Research at Harvard (Deslauriers et al., 2019) found support that students prefer and perceive they learn more from traditional lectures; however, according to the study they actually performed better on tests following active learning.

A framework for understanding the practice of leadership necessary to be effective in today’s world needs to integrate well-established methods, such as presentations of ideas through lectures, discussion-based seminars, simulations, coaching, reflective writing, and the case study method (Parks, 2005). In addition, the study of and development of leadership competence should include both self-awareness and social awareness as a part of leadership development; the latter being essential for understanding interactions between leaders and followers in organizational settings (Schyns, et al., 2011). Parks (2005) acknowledges that while methods such as case studies have value, students learn best from their own experiences, rather than the experiences of others (cases). Therefore, the “case-in-point” approach uses students’ own experiences-using the classroom as a studio-labo-ratory-for working through the types of challenges faced in the workplace. For example, the use of cases, simulations, project-based learning could be about more than just solving the issue, but about the process of leadership used by team members that resulted in either failure or success. In fact, helping students to understand the process they went through could potentially be the most important lesson learned.

Limitations of the Study

The present study is not without its limitations. First, because the data was collected from a single source, common-method bias cannot be ruled out as a possible explanation for the obtained relationships between the variables studied.

A second limitation is that the respondents to the study were largely males (87.1%) and members of a military unit. Future studies should involve a balance of males and females, as well as broader organizational membership. However, there is probably no other organization in the world that spends as much time developing leadership among both non-commissioned officers as well as commissioned officers-in fact, most promotions are contingent not only on performance but on completion of leadership training.

A third limitation of the study is that causality cannot be inferred from the correlational data collected for this study. However, the intent of the present study was to examine the relationships between followers’ perceptions of leader’s power, leader’s behavior, and followers’ motives for conformity, and the model depicted in Figure 1 merely suggests a theoretical framework in which these relationships exist.

A fourth limitation of the study is the use of multiple regression techniques that imply there is no measurement error in the variables studied (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The presence of measurement error in the mediator tends to underestimate the effect of the mediator and overestimate the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, which may result in successful mediation being overlooked. However, based on the results obtained in the regression analyses, this does not appear to be a problem since the independent variables (power bases) were non-significant in the presence of leader’s behaviors.

References

- Arenas, F. J., Connelly, D. A., & Williams, M. D. (2018). Developing your full range of leadership: Leveraging a transformational approach. Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182.

- Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

- Bass, B. M., and Avolio, B. J. (1990). Multifactor leadership questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press.

- Bass, B. M. (2008). Handbook of leadership: A survey of theory and research, 4th Ed. New York: Free Press.

- Bass, B. M., and Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving Organizational Effectiveness. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588-606.

- Bycio, P., Hackett, R. D., & Allen, J. S. (1995). Further assessments of Bass’ (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 468-478.

- Clifton, J. & Harter, J. (2019). It’s the Manager. New York, NY: Gallup Press.

- Conger, J. A. (1993). Max Weber’s conceptualization of charismatic authority: Its influence on organizational research. Leadership Quarterly, 4, 277-288.

- Cuddy, A. (2020). George Floyd: Five pieces of context to understand protests. doi: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-can-ada-52904593

- French, J. R., & Raven, B. H. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Deslauriers, L., Logan S. McCarty, Kelly Miller, Kristina Callaghan, & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821936116

- Falbe, C. M. & Yukl, G. (1992). Consequences for managers of using single influence tactics and combination of tactics. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 638-652.

- Hinkin, T. R., & Schriesheim, C. A. (1989). Development and application of new scales to measure French and Raven’s bases of social power. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 561-567.

- Hollander, E. P. (1978). Leadership dynamics. New York: Free Press.

- Hollander, E. P., & Offermann, L. R. (1990). Power and leadership in organizations: Relationships in transition. American Psychologist, 45, 179-189.

- House, R. J. (1977). A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In J. G. Hunt & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership: The cutting edge. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Jorge, K. (2021). Mural honors Nashville police officers who ran to danger, saved lives before bombing. doi: https://fox17. com/news/local/mural-honors-nashville-police-officers-who-ran-to-danger-saved-people-before-bombing-christmas-explosion-i-believe-in-heroes

- Kelman, H. C. (1953). Attitude change as a function of response restrictions. Human Relations, 6, 185-214.

- Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, Identification, and internalization: Three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2, 51-50.

- Kelman, H. C. and Lawrence, L. H. (1972). Assignment of responsibility in the case of Lt. Calley: Preliminary report on a National Survey. Journal of Social Issues, 28, 177-212.

- Kipnis, D. (1984). The use of power in organizations and in interpersonal settings. Applied Social Psychology Annual, 5, 179-

- 210.

- Lussier, R.N. & Achua, C.F. (2016). Leadership: Theory, application, and skill development. Boston, MA: Cengage.

- Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396.

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Parks, S.D. (2005). Leadership can be taught. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Percy, P. M., (1999). Relationships between interpersonal power and followers’ satisfaction: A leadership perspective. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting (Chicago).

- Percy, P.M. & Tepper, B.J. (1994). Downward influence tactics and follower conformity: An empirical investigation. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting (Dallas).

- Schyns, B., Kiefer, T., Kerschreiter, & Tymon, A. (2011). Teaching implicit leadership theories to develop leaders and leadership. Academy of Management Learning & Education,

- Shaffer, B., Percy, P. M., & Tepper, B. J. (1997). Further assessment of the structure of Hinkin and Schriescheim’s measures of interpersonal power. Educational and Psychological Measurement.

- Tepper, B. J. (1993). Patterns of downward influence and follower conformity in transactional and transformational leadership. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Proceedings, Journals.AOM.org.

- Tepper, B. J., Eisenbach, R. J., & Percy, P.M. (1995) Downward Influence Processes. Unpublished manuscript.

- Tepper, B. J., & Percy, P. M. (1994). Structural Validity of the multifactor leadership questionnaire. Educational and Psycho-

- logical Measurement, 54, 734-744.

- Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organizations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wiltermuth, S.S. & Flynn, F.J. (2013). Power, moral clarity, and punishment in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 56, 1002-1023.

- Yukl, G. A. (2002). Leadership in organizations, 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Yukl, G., & Falbe, C. M. (1991). Importance of different power sources in downward and lateral relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 416-423.

- Yukl, G., & Tracey, J. B. (1992). Consequences of influence tactics used with subordinates, peers, and the boss. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(4), 525–535.